Choosing Our Battles: Why the feminist movement needs to stop arguing and support the decriminalisation of sex work

Choosing Our Battles: Why the feminist movement needs to stop arguing and support the decriminalisation of sex work

In May, as part of our zine project go it alone (together), Emily Davidson and I gave a workshop at the Montreal Anarchist Bookfair: “The Struggle for Reproductive Autonomy: From underground abortion collectives to the fight to decriminalize sex work.” Before we had even left our home city of Halifax, we received a phone call from one of the bookfair’s organisers to discuss some of the conflict that had arisen in the feminist movement in Quebec around the decriminalisation of sex work. The organiser explained that there was a strong movement in support of the abolition of sex work in Montreal and Quebec.

Later, Emily and I spoke at length about strategies for addressing possible disruptions at the workshop, as well as a number of ways to ensure an effective discussion could be had recognising and respecting divergent views. There was no vocal presence from the “sex work abolitionists” at the workshop and largely the discussion was focused on the need for more inclusive, accessible, queer- and trans-positive health care providers focused on a model of informed consent with regards to care.

But we also had to ask ourselves – what does “abolishing” sex work mean?

Abolition v. Prohibition

Abolish, in my understanding of the word, means to eliminate, to end, maybe even to destroy. This is the way I use the word when I speak with my political allies about abolishing the prison system. I mean there should be no more prisons. I also know that this is a long and difficult process – one that involves struggle in many forms, and one that posits social revolution.

Near the end of her book, Are Prisons Obsolete, Angela Davis explains:

“[P]ositing decarceration as our overarching strategy, we would try to envision a continuum of alternatives to imprisonment–demilitarization of schools, revitalization of education at all levels, a health system that provides free physical and mental care to all, and a justice system based on reparation and reconciliation rather than retribution and vengeance.

The creation of new institutions that lay claim to the space now occupied by the prison can eventually start to crowd out the prison so that it would inhabit increasingly smaller areas of our social and psychic landscape. Schools can therefore be seen as the most powerful alternative to jails and prisons.” (pp.107-108)

The struggle to abolish prisons, then, is an active struggle that works to shrink the role prisons have in our society – the role they play in the core of our understandings of justice.

Coming from this position, and having read a lot written by those who oppose sex work, I have a series of questions for “abolitionists” who are currently opposing the decriminalisation of sex work in Canada.

- What would abolishing sex work actually look like?

- How, in practical terms, does prohibition work towards the goal of abolition?

- Where has prohibition been an effective tool for changing social conditions or altering social practices?

These are not rhetorical questions; they are genuine questions I would like to see answered by those people who are currently opposing the decriminalisation of sex work. There are more questions that run through my mind: What kinds of sex work would/should be prohibited? What about strippers, professional dominatrices, webcam girls, freelance fetish workers, burlesque perfomers? Who should be criminalised? Sex workers, johns, madames, members of the kink community, bachelor parties, bar/club owners? I would like those opposing sex work decriminalisation to speak plainly – in materialist terms – about how that fight fits with their goals, strategies, and tactics.

In the current political climate of our “tough on crime” Conservative government, I can imagine the horrors of a “war on sex work:” the most marginalised sex workers and johns thrown into cages, perhaps first brutalized by the police. I can see the way that those who are most vulnerable to police violence – sex workers of colour, trans sex workers, survivor sex workers, Aboriginal sex workers, sex workers without status, underage sex workers – would be treated, forced further and further underground and out of sight. I can see it because it happens already. I can see it because these are patterns that pop up elsewhere: in our mental health system, the way that people struggling with addictions are treated, the way that survivors of domestic violence continue to be treated.

If the Canadian Border Service Agency can go into shelters and crisis centres searching for non-status survivors of abuse, why do we think we can trust them to treat non-status and/or trafficked sex workers with dignity, respect, and care?

The end of sex work will not come by way of the law, and as with many other things, the law continues to work in the interests of those who have power, not the oppressed.

For decades, feminists have repeated over and over that criminalising abortion will not stop abortions. Where abortions are needed, they happen – often with terrible consequences. Women die when abortion is not accessible. How many times have we repeated the chant, “Pro-life that’s a lie, you don’t care if women die,” in opposition to anti-choice forces?

So, why now do we think that prohibition of sex work would stop trafficking or violence against sex workers?

The Discussion We Cannot Have… Yet

There are valid political, ideological, and moral discussions feminists need to have on their analyses of sex work, of labour, of the police and prisons, and a hundred other facets of the role of sex work in our society. The time for those discussions is not now.

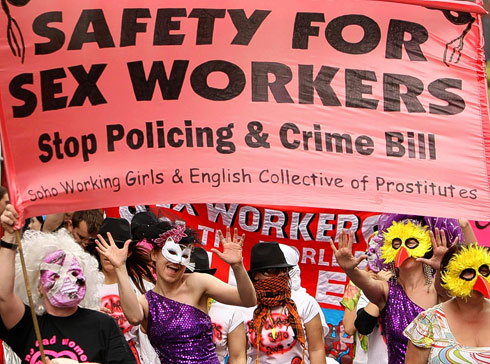

The decriminalisation of sex work could actually open up space for a larger, more creative discusssion to be had about sex work, sex workers, patriarchy, the criminal legal system, and state control of women’s bodies. We could start talking about new models for sex worker organising. We could think of new ways of approaching anti-violence work in our communities. We could think critically about what role (if any) we see the legal system having in our fight for a more just and equitable world.

It is in these discussions that we could actually talk about abolishing sex work because the question before the courts right now has nothing to do with abolition and everything to with prohibition.

I am prepared to have those discussions, debates, arguments. I am willing to be open and to challenge myself and to listen during what would be challenging times. But I won’t do that until this court case is settled because now my energy needs to be there, supporting sex workers in my communities – most of them women and queer and trans folk – in this battle against dangerous and oppressive laws.