OPINION: The narrowness of official support for racial justice

OPINION: The narrowness of official support for racial justice

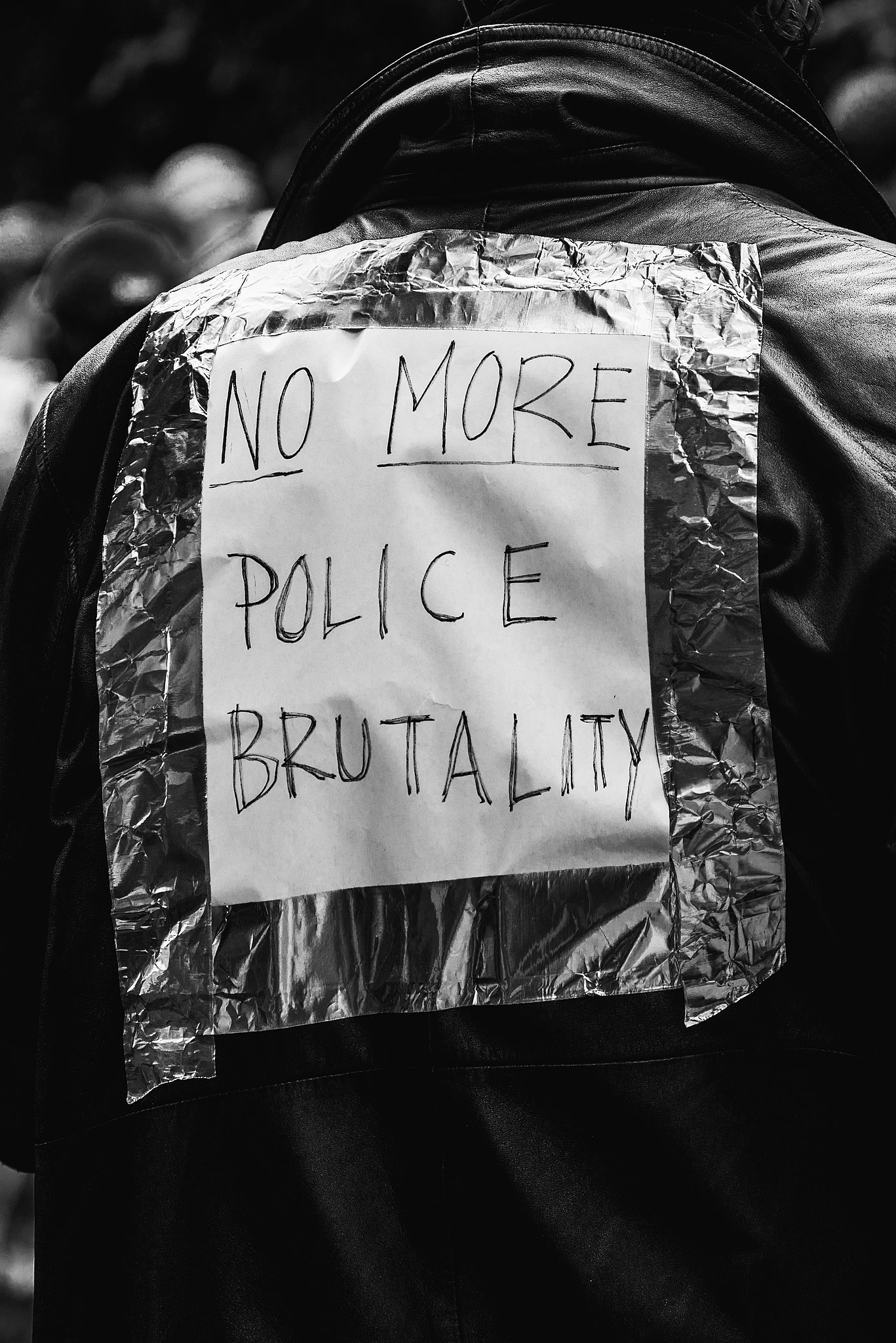

In the two years since George Floyd’s murder at the hands of now-indicted Philadelphia police officer Derek Chauvin, we have witnessed the speed with which governments can elevate activists and their causes. We have also witnessed how quickly these sentiments can be reversed. Despite all of the platitudes and solemnly proclaimed promises of change, activists continue to find themselves facing the brunt of police violence.

George Floyd’s death was far from the first killing by police in the U.S. to ignite protests and activism here in Canada. The 1992 Los Angeles riots, sparked by the beating of Rodney King, and later the murder of Latisha Harrins, emboldened protestors in Toronto to respond to the murder of Raymond Lawrence by police. And the acquittal of George Zimmerman for the killing of Trayvon Martin has been compared to the Coulton Boushie case, where the Indigenous teen’s killer was set free. The Trayvon Martin case in particular ignited a wave of protests in Toronto, Vancouver, and other cities, and catapulted organizations like Black Lives Matter (BLM) into the public sphere in Canada.

In this country, there are many who simply do not believe that racism is a Canadian phenomenon. Some claim that the calls for justice here are little more than imitations of the righteous struggles south of the border – including Ontario Premier Doug Ford, who eventually walked back his comments that Canada does not have the kinds of systemic racial problems that plague the U.S. But the comparisons are so powerful and the grassroots momentum flows across the border with such ease precisely because of how deeply rooted the same issues are here.

The activism of Black and Indigenous communities has driven these waves of protest. The mobilizations after George Floyd's death were some of the most disruptive and effective cross-continental protests we have yet seen around policing and racism. Crucially, they demanded solidarity from government officials in ways that officials could not ignore.

In Ottawa, during a BLM solidarity protest, Justin Trudeau knelt in the presence of protestors. A couple of weeks later, he would support a declaration signed by over 100 Black MPs and allies, demanding an end to systemic racism. In addition to acknowledging systemic racism towards Black and Indigenous communities in Canada, the declaration also called for the collection of race-based data, the elimination of mandatory minimum sentences, and the “restructuring of law enforcement and budgets.” While this declaration fell short of demanding the formal defunding of police, it was a testament to the work of activists who in previous years had shut down city centres to demand change.

It is perhaps because of the effectiveness of these activists that we are now seeing a swift backlash. Black and Indigenous issues in Canada are becoming more mainstreamed. They are on the political agenda, and are key parts of party platforms and campaigns. And we have all seen the dramatic displays of solidarity from governments and from public and private sector institutions. Yet alongside these shows of solidarity, we continue to see the heavy-handed use of police against the same protestors that pushed these issues to the forefront.

For example, just months after the Primer Minister knelt in the streets of Ottawa, 12 Indigenous and Black activists were arrested for a multi-day demonstration on those very same streets. Among those arrested were organizers from the Justice for Abdirahman Coalition. Their demands included limiting the police budget and greater public investment in education and housing.

Or take Hamilton, Ontario, where primarily Black advocates have lead the charge for the removal of student resource officers in schools, demanded the defunding of police, and protested against encampment evictions. Despite a statement of solidarity for victims of racism and discrimination by Mayor Fred Eisenberger, he denied the pervasiveness of racism in policing. Hamilton police also came under scrutiny for their treatment of encampment support advocates. Community members requested the SIU investigate the use of force and arrests of encampment protestors after witnessing a young woman held down by the same shoulder pin used against George Floyd.

In an interview with Robyn Maynard, author of Policing Black Lives: State Violence in Canada from Slavery to the Present, she highlighted policing as the carceral arm of the state. She added, “We saw the symbolism of [Toronto police chief] Mike Saunders and Justin Trudeau taking a knee. [They] claimed that Black Lives Matter, but it’s the exact opposite…. Now they are standing silently by while that same movement is under attack.”

The continual use of force by police against protestors reveals that behind these sometimes dramatic declarations of solidarity with activists, there is little substance. While officials are willing to acknowledge that systemic racism is an issue in policing, they are reluctant to acknowledge that racialized activists on the frontlines are frequently targets of police confrontation. This separation of Black and Indigenous issues from Black and Indigenous activism conveniently erases the very voices that have brought racism to the forefront of contemporary politics. It has also led to insidious policing practices against activists.

For example, following encampment eviction protests in Hamilton and Toronto, there were reports that bail conditions barring people from protest are being imposed. While in Hamilton these conditions were later repealed, elsewhere many people feel like their right to protest is under threat. Worse still, the potential for deadly confrontation between police and activists of colour remains when policing practices go unchallenged. Unsurprisingly, protections for activists have not appeared on the political agenda.

Activists have not only been the first to sound the alarm but often the first to develop crucial community-based solutions. Enduring systemic change, like that promised by politicians in 2020, demands more than symbolic allyship – it demands confronting law enforcement practices towards activists and protestors. If politicians are serious about preventing tragedies like that of George Floyd, Andrew Loku, Abdirahman Abdi, Clive Mensah and many more, they should start there.