Students rise to ‘decolonize’ campus

Sep 20, 2012

Students rise to ‘decolonize’ campus

This post has not been approved by Media Co-op editors!

This year’s orientation week at the University of Ottawa featured a few activities that went against the grain of debauchery commonly found on campuses across the country in early September.

On Sept. 4, Phillip “Rohetiio” White-Cree of the Mohawk Nation of Akwesasne and Sahra MacLean of the Métis Nation spoke to room of students during an event entitled Indigenous Post-Secondary Perspectives: An Alt 101 Decolonization Workshop and Traditional Meal.

In the spirit of traditional Mohawk culture, a meal of corn soup, frybread, and strawberry drink satisfied the bellies of approximately 40 attendees.

“It is extremely important to organize in our local context, here on unceded Algonquin territory,” says Nicole Desnoyers, a Métis student and a campaigns organizer of the Student Federation of the University of Ottawa (SFUO).

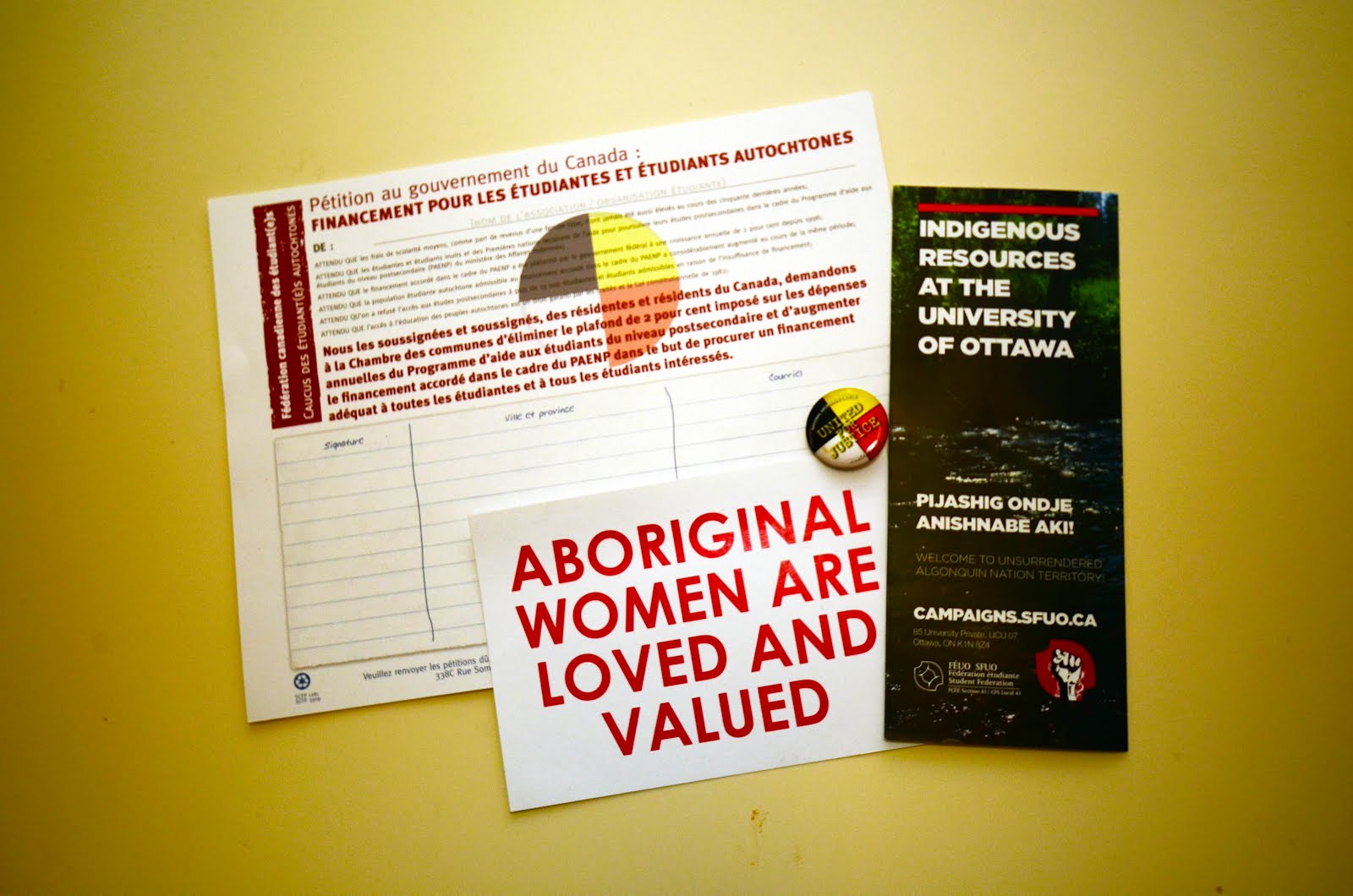

The event, organized by the Campaigns Department of the SFUO, the Ontario Public Interest Research Group (OPIRG), and the Indigenous and Canadian Studies Students’ Association, sought to inform both first-year and returning students of their collective responsibilities towards Indigenous peoples, according to Desnoyers.

She says the panel discussion aimed to educate students on the diversity of Indigenous identities and the meaning of treaty relationships.

MacLean, a Métis woman from Alberta and current Chair of the National Aboriginal Caucus of the Canadian Federation of Students, discussed the many barriers to education Indigenous students face across the country.

According to MacLean, the federal government’s Post-Secondary Student Support Program (PSSSP), which provides financial support to Indigenous students, is fraught with problems. Only “Status Indians,” which include those Métis, Inuit, and First Nations registered by Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) under the Indian Act, are eligible for tuition support.

This neglects Non-Status students unable to obtain a Certificate of Indian Status because they cannot access the required information demanded of them by the status application process. This is a familiar story, for example, for many Indigenous children put in foster care or adopted out under the child welfare system.

Thus, the number of Indigenous students able to access financial support for education is limited.

“When we are talking about numbers, it is important to reflect on who has control of those numbers. If we are estimating those numbers based on students with Status cards, we are working within the structures of colonialism that dictate who is ‘allowed’ to be Indigenous or not,” says Desnoyers.

MacLean spoke about other funding discrepancies within the PSSSP. While tuition goes up an average of five percent per year in Ontario for domestic students, federal funding increases for the PSSSP have been capped at two percent per year. This has led to a significant gap in funding for Indigenous students.

The panel’s second speaker, Phillip “Rohetiio” White-Cree, spoke on the history and usage of the Two-Row Wampum Belt. He provided the audience with a compelling history lesson on treaties signed between First Nations and Dutch settlers.

The event was held as part of a broader campaign recently launched on campus called ARISE, which stands for Anti-violence, Recognition, Indigenization, Solidarity and Education to all. The campaign is an exciting new initiative organized by a variety of campus partners, including the Indigenous Students’ Association, the SFUO, and the Graduate Students’ Association (GSAED).

According to Desnoyers, “It is our responsibility to learn the factual history of this land, of the vicious realities of colonialism, and to address the barriers on our campus as well as work towards healing.” The campaign seeks to facilitate this process.

“The University of Ottawa largely ignores Indigenous students and their needs,” she says. “This campaign has been a long-time coming, and is a necessity to create accountability between non-Indigenous structures and Indigenous nations.”

As outlined in the campaign structure developed by ARISE, the project seeks “to end the physical, verbal, lateral and institutional violence targeted against Indigenous people at the University of Ottawa.”

According to William Leonard Felepchuk, coordinator of university affairs for the Indigenous and Canadian Studies Students’ Association, the association has received reports of racism on campus.

“There have been incidents of Indigenous students experiencing extremely racist language from professors, being verbally attacked by professors. There’s been a pattern of callous treatment of Indigenous students and a lack of understanding of the challenges they face on the part of the administration and individual administrators,” he told the Leveller.

In addition to challenging racism, the ARISE campaign calls for the “Indigenization of academia at the University of Ottawa: more indigenous studies taught by Indigenous instructors, including programs in Indigenous languages.”

There is an undergraduate Aboriginal Studies program at University of Ottawa, and there are a variety of courses offered by the university related to Aboriginal culture within a variety of disciplines. However, many of the professors in the program are not themselves Indigenous.

This raises questions about just who is producing knowledge on Aboriginal issues in the academic community. It affects how the experiences of Indigenous peoples are represented in the classroom.

Currently, the University of Ottawa offers one language instruction course, through the Department of Linguistics, in Indigenous language. The language taught varies from year to year, but has recently centred on Cree. Across disciplines, courses are taught in French and English, but none are offered in Indigenous languages.

Desnoyers says that she has slowly begun the process of reclaiming her own Indigenous history. For her, exposing the failures of Canada’s education system means unearthing the history of colonialism in Canada.

“Four centuries of colonialism have left us with a post-secondary education system that silences the histories of Indigenous people in Canada. Students do not have access to their own stories, the teachings of their nations or the true history of colonialism.”

This article first appeared in the Leveller volume 5, issue 1.