For Settlers - Understanding Treaty One in the Context of Idle No More

For Settlers - Understanding Treaty One in the Context of Idle No More

If #Idlenomore is successful in the coming weeks there will be lots of talk about how to honour the treaties and build a new relationship between grassroots settlers and indigenous peoples.

As we move forward, we also need to look back and understand what actually happened at the time of making treaty between the crown and First Nations.

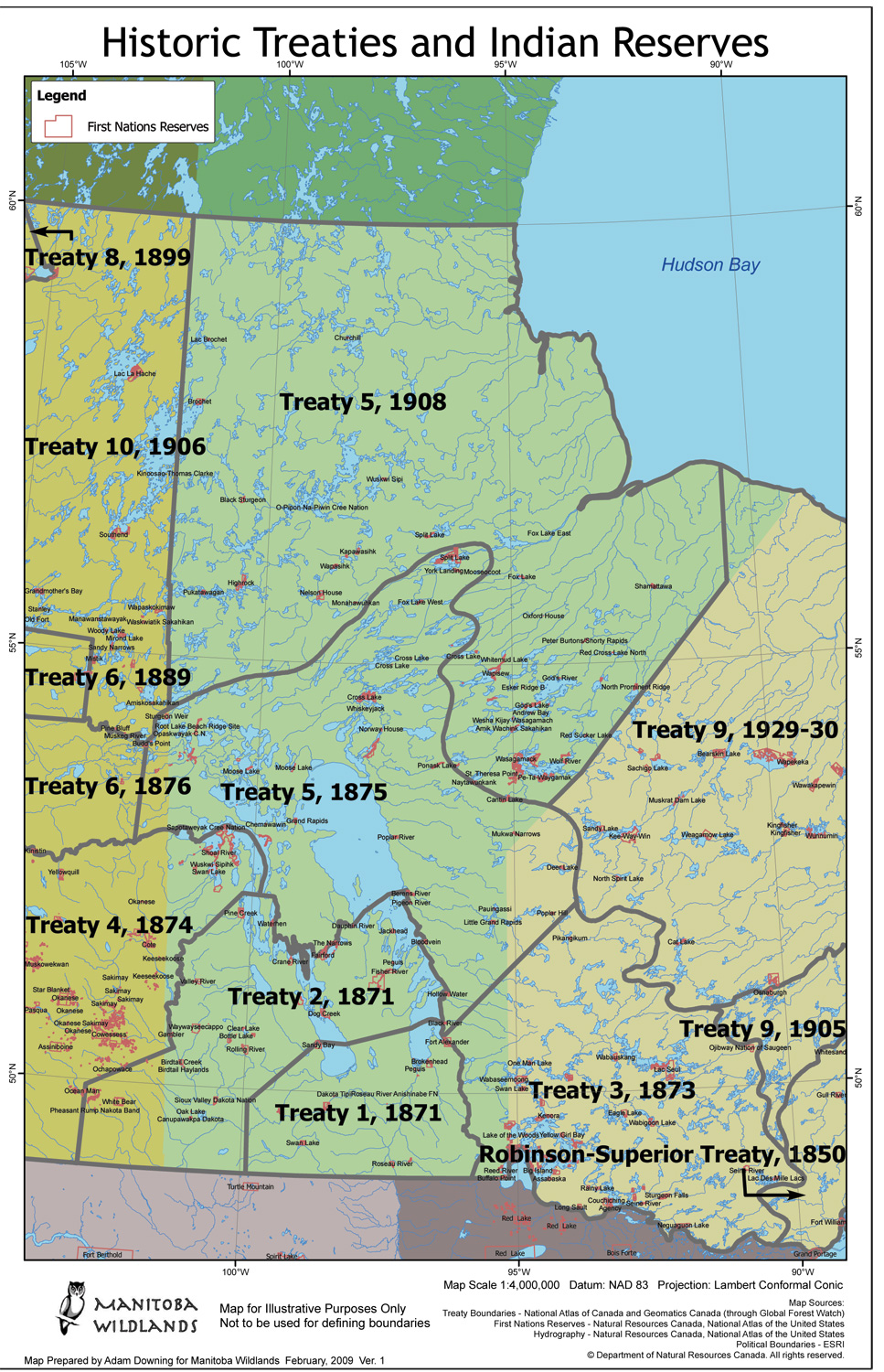

Treaty One is the treaty land Winnipeg sits on and we need to know the history of this place to understand how to move forward.

The Evolution of the Indigenous Negotiating Position

As Jean Friesen argues in Magnificent Gifts: the Treaties of Canada with the Indians of the Northwest 1869-1876 we must understand Indigenous agency because it is key to understanding how the process of negotiating Treaty One took place. In other words, we need to know what Indigenous people actually offered and accepted during the negotiation process to understand how we can walk with justice now as we build a new Canada and struggle against the conservatives.

Looking into the play-by-play of the treaty process is essential to understanding the spirit and intent of the Indigenous peoples at the time. Friesen argues that understanding Indigenous agency helps to provide a fuller picture of what transpired, and prevents us from viewing Indigenous peoples as ignorant and helpless victims.[1] To understand the spirit and intent of the Indigenous peoples it is necessary to understand what transpired in the negotiations.

The original Indigenous negotiating position which was presented at the arbitration is far different from what the Anishinaabeg were compelled to settle for at the end of the negotiations. Most of this history is hidden from commentaries on Indigenous peoples by settler political scientists or even what makes it into much of the popular literature on liberal approaches to treaties or recognition.

D. J. Hall, in his article “A Serene Atmosphere”? Treaty 1 Revisited, provides as an appendix the record of the negotiations released by the Manitoban on the 5th and 12th of August 1871.

The Indigenous peoples initially presented claims for land that totaled almost two-thirds of the provincial land. The reserves were in places of their choice and were very large.[2] The government promised them the right to hunt on any unoccupied lands,[3] and that Métis would receive additional land tenure and compensation, not included in these negotiations.

What is clear from reading the partial transcript of the negotiation is the Indigenous peoples entered negotiations with the understanding that they would retain the majority of their lands.

Secondly, it is clear that the Canadian government entered negotiations with the position that it had the right to determine how much land would be left for the Indigenous and that it was already inevitable that the settlers would take the land they needed.

The Canadian representatives felt they were the ones offering the Indigenous the land, rather than the inverse. The Canadian government essentially threatened a take it or leave it agreement with the Indigenous.[4] In my analysis this is a threat of annexation without compensation.

The Hidden Indian Acts

Historian Sarah Carter argues that the Canadian government failed to warn or explain the jurisdiction and implementation of the Indian Acts in any of the negotiations. In the case of Treaty One the negotiations made no mention Gradual Enfranchisement Act (1869). Subsequent negotiations did not mention the Indian Acts passed in the later 1870s.[5]

What is central to understand is that the Canadian state was asserting jurisdiction over Indigenous peoples inside its borders and in negotiation refraining from informing the Indigenous peoples about legislation it would be subject to that was passed 2 years previous to signing treaty. In other words, they were lying by omission or being deceitful.

This racialized legislation which allowed Canada to govern Indigenous nations inside its claimed territory was hidden from Indigenous peoples at negotiation. The Gradual Enfranchisement Act was the first to contain the imposition of western democracy on Indigenous peoples. This in my analysis does not qualify as a context from which signing was done with informed consent. In other words, Indigenous people never agreed to an Indian Act.

To recap what we’ve learnt so far: the Indigenous negotiating position was not fully informed of the context in which it would be subject to, and was forced to respond to the threat of annexation without compensation by the Canadian representatives.

Within these parameters the Indigenous negotiating position shifted dramatically from one of land maintenance to that of attempting to secure a guaranteed income for its members to smooth the forced transition from a gatherer and hunting society to an agricultural society.[6]

In other words, the Indigenous gave up trying to negotiate to protect their land from Canada because Canada insisted on taking it all under threat of force and a flood of settlers.

We need to understand this was a conscious response on the part of the Indigenous spokespeople when they came to realize that nowhere in this negotiation was there any space for their original demands.

What I also want to make sure is clear this ought not to be considered the spirit and intent of the Indigenous position upon coming to engage in treaty. The spirit and intent of the Indigenous position upon beginning negotiations of Treaty One was to maintain their way of life and the vast majority of their land-base forever.

Only upon recognizing this was not possible because of the Canadian state’s position did they change their negotiating position.[7] These changes in no way ought to reflect or come to represent the overall intention of the Indigenous or be the only positions studied when determining what constitutes reparations or justice.

Put differently, we need to respect and strive for justice in a way which is responsive to what Indigenous peoples wanted before the threats of annexation by the Canadian government.

It is also important to acknowledge that what made it into the text of Treaty One and what was actually agreed upon differ significantly according to Indigenous peoples, the government, and historians. Hall, Carter, Miller, and Friesen all agree that in addition to the text there were outside promises that were left out of the Treaty.[8]

A memorandum from the Minister of the Interior, dated April 30th 1875, confirms that outside promises were made and provides the Canadian governments strategy for mitigating unrest and disappointment of its failure to honour all the promises it made during negotiations.[9] However, the government refused to acknowledge it had failed to meet its obligations.[10]

Like the residential schools settlement the money accepted by Indigenous peoples for these outside promises came with the condition that they were in the future unable to litigate or demand more compensation for the injustices they suffered.

To recap: the Canadian government asserted the right to unilaterally decide on the portion of lands, broke outside promises, and did not fully inform the Indigenous peoples of legislation they would be subject to upon signing.

I still do not know where the Canadian state’s assertion of jurisdiction comes from other than power. Canada was acting like a bully. This is the foundation of our country, one Harper actually represents well.

Why did they sign?

Understanding why the Indigenous chose to sign Treaty One despite the position asserted by the Canadian state’s representatives is central to understanding the terms of Treaty.

David McCrady provides a novel interpretation of the circumstances surrounding the Indigenous decision to sign Treaty One. McCrady first argues that to understand Indigenous actions one has to dispense with the national myth of the peaceful west.

McCrady argues:

This explanation offers no insight into what motives Aboriginal peoples living in Canada had for maintaining peace. Native peoples are portrayed as the passive victims of the white man’s actions, incapable, it would seem, of affecting the level of violence between themselves and the newcomers. Native peoples made up the vast majority of the population of the Canadian Northwest. Had a single group decided to launch a concerted attack against Canadian immigrants, the result would have been a disastrous blow to Canada’s expansionist goals … they remained peaceful, but not because they were overawed or placated by Canada’s “orderly, well-planned, and honourable policy.” They had their own reasons for establishing peaceful relations.[11]

McCrady’s argument fits with Friesen’s idea about understanding Indigenous motivations in the actual negotiations themselves. Both of these authors are attempting to provide us with an understanding of Indigenous peoples motivations so we understand what actually took place from both sides. Friesen argues the basic intention of the Indigenous was to assure economic security.[12]

McCrady asks us to consider how the wider geopolitics of Turtle Island at the time would have influenced Indigenous strategy in deciding to treaty and on what terms.

McCrady shows Indigenous peoples saw Canada as the weaker of the two European derived states and chose to pursue peace with Canada in the context of the United State’s expansionism and wars against Indigenous populations. The Indian wars were happening to their relatives right on the plains.

Moreover, McCrady argues that Indigenous peoples chose to negotiate with Canada because they were not a military threat at the time of signing. They were pushed into the situation by the actions of the Americans.[13]

J. R. Miller’s analysis of Canada’s military capacities at the time agrees with the assessment of McCrady, Miller argues that Canada had neither the money nor ability to project force at the time of signing Treaty One, the Police for instance did not arrive until 1874, nor was there any railway to move troops across the prairies at the time.[14]

It is my understanding it was in the interest of the Indigenous to sign a treaty with the Canadians. When the Canadians refused to treaty on Indigenous terms the Indigenous position was also influenced by the need to assure peace in the face of an American aggressor.

Accepting Canadian terms was about gaining peace first and working out the problems later.

It is important to understand that Indigenous agency played an important role in the situation that led to the signing of these documents, and that part of the intent and spirit of Indigenous peoples was to assure themselves protection against American imperialism.

Where do we go from here?

When we considering using treaties in contemporary times, understanding the rejection of American expansionism needs to remain prominent in the analysis and future content of political relationships we aim to build. In contemporary times American corporations and their Canadian spawn are central in the exploitation of Indigenous lands, it seems reasonable to assume this type of circumstance was exactly what the Indigenous were attempting to avoid.

Every settler needs to think long and hard about how we write the new chapters of this story. They need to feel their way through the injustices and put aside the guilt it can cause. Deep inside Canadian history there is an Indigenous constitution of Canada and it is revolutionary. Our story has to be finding it together and writing the chapters which we always intended.

If #idlenomore is going to solve the problem and not just be another reactive protest it needs to focus on a process of rekindling the treaty relationship between settlers and Indigenous peoples at the grassroots.

Settlers who want to jump on the bandwagon need to focus on building permanent grassroots organizations of people committed to the original narrative of treaties. Not just showing up at the protests hosted by Indigenous peoples. We have our own battles to fight too!

We need to integrate support for Indigenous struggles into our own workplace and community issues, whether food security, union issues, or environmental protection.

Going to support a protest by Indigenous people is the easiest thing you can do. It will not rewrite the story. What will is building permanent anti-colonial forces which will make Canada ungovernable until the original intent of treaties are honoured.

[1] Jean Friesen, “Magnificent Gifts: the Treaties of Canada with the Indians of the Northwest 1869-1876,” in Richard Price, (ed.), The Spirit of the Alberta Indian Treaties, Edmonton, AB: University of Alberta Press, 1999, pg. 204-205.

[2] D. J. Hall, ““A Serene Atmosphere”? Treaty 1 Revisited,” the Canadian Journal of Native Studies, 2, 1984, pg. 325, Appendix 346-349. Accessible here: < http://www2.brandonu.ca/library/cjns/4.2/hall.pdf >

[3] Hall, ““A Serene Atmosphere”? Treaty 1 Revisited,” Appendix pg 345.

[4] Hall, ““A Serene Atmosphere”? Treaty 1 Revisited,” pg. 325-326.

[5] Sarah Carter, Aboriginal People and Colonizers of Western Canada to 1900, Toronto, ON: University of Toronto, 1999, pg. 118.

[6] Hall, ““A Serene Atmosphere”? Treaty 1 Revisited,” Appendix, pg. 354-355.

[7] Friesen, “Magnificent Gifts,” pg. 212.

[8] Hall, ““A Serene Atmosphere”? Treaty 1 Revisited,” pg. 324, and Carter, Aboriginal People and Colonizers of Western Canada to 1900, pg. 122, and Friesen, “Magnificent Gifts,” pg. 212, and J. R. Miller, Compact, Contract, Covenant: Aboriginal Treaty Making in Canada, Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2009, pg. 164-165.

[9] Government of Canada, Treaties 1 and 2 between Her Majesty and the Chippewa and Cree Indians, Treaty Relations Commission of Manitoba, 1957, pg. 3-5,

< http://www.trcm.ca/PDFsTreaties/Treaties%201%20and%202%20text.pdf > Accessed Oct 13th, 2011.

[10] Miller, Compact, Contract, Covenant, pg. 165.

[11] McCrady, Beyond Boundaries, pg. 88-89.

[12] Friesen, “Magnificent Gifts,” pg. 207.

[13] McCrady, Beyond Boundaries, pg. 93-96, 101.

[14] Miller, Compact, Contract, Covenant, pg. 155-156.